Why Does My Shoulder Hurt?

The shoulder is one of the most used joints in the body. It is also the most inherently unstable joint in the body. Before we can understand why the shoulder is hurting, we need to understand the basic anatomy of the shoulder first.

The shoulder is a ball-in-socket joint, meaning that one surface of the shoulder is a ball (humerus), and the other surface is a socket (glenoid). The medical name for the shoulder is the Glenohumeral Joint - it’s the joint where the glenoid and the humerus come together. The socket is part of the shoulder blade, and the ball of the humerus rolls and glides in the socket with all arm movement. The socket itself is a very shallow surface - it’s pretty flat, like a saucer. Because of the relative flatness of the socket, the humerus has ample space to move around - giving us the ability to reach in all directions, throw a ball, fasten a bra behind us, and more. The down side of the shallow surface of the joint is that, without stability from muscles and other tissues, it’s pretty easy for the ball to slide out of the socket.*

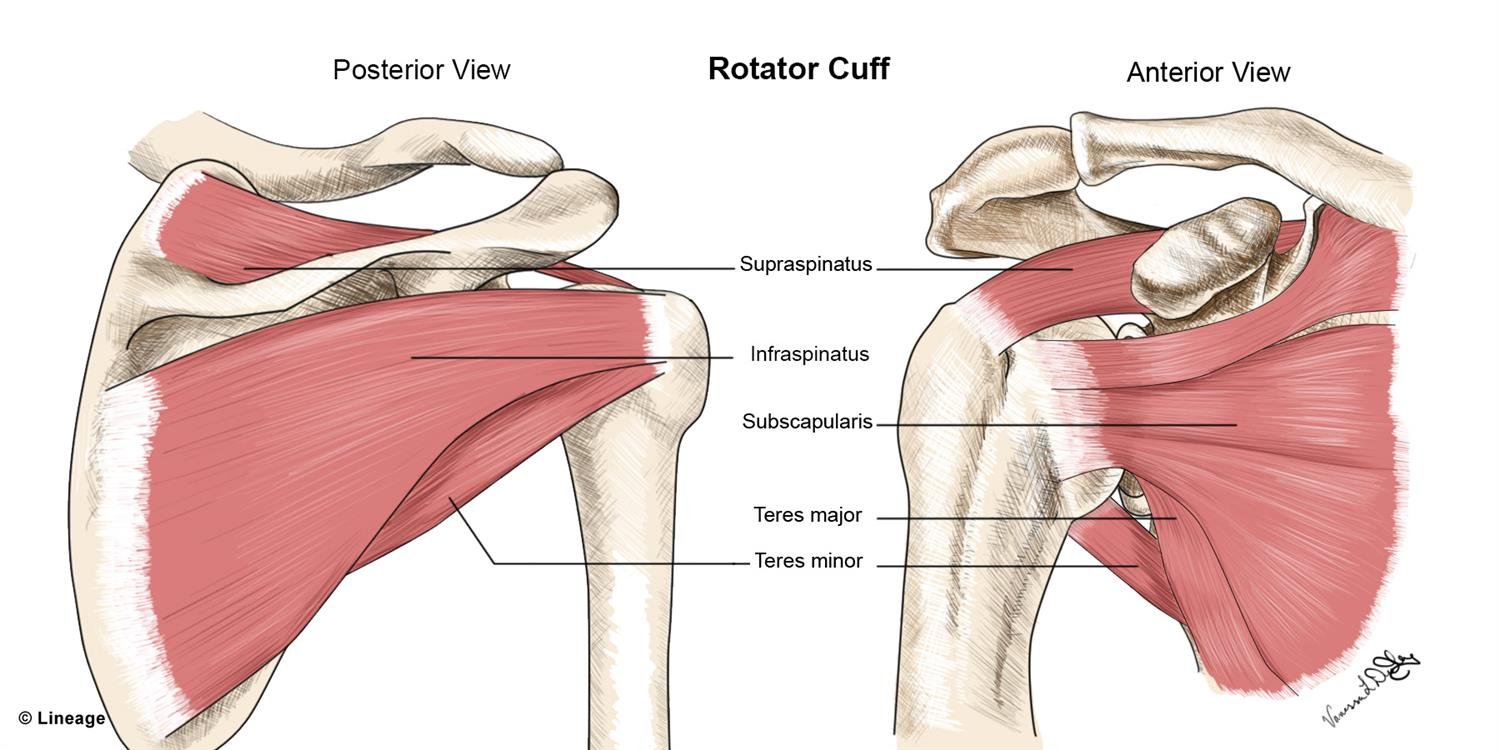

Thankfully, our shoulders are designed with strength, stability, and mobility as equally important partners. The stability of our shoulders comes primarily from a group of 4 muscles (Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Subscapularis, and Trees Minor) called the Rotator Cuff. This group originates in various places on the shoulder blade and extends out toward the top of the arm, creating almost a hand holding the ball in the socket.

All shoulder movement is controlled by the rotator cuff. It maintains stability of the ball in the socket, and allows for efficient movement of the arm. Often times, however, we don’t focus on the strength of the rotator cuff, and instead turn our attention to better known (and more visible) muscles in the shoulder and arm: the biceps, lats, deltoid, and upper traps. Unfortunately, focusing only on these superficial muscles, we tend to lose strength and stability of the rotator cuff, leading to incorrect mechanics in the shoulder joint. These mechanical changes are what leads to pain and injury.

The muscle most commonly involved in “idiopathic” shoulder pain (or shoulder pain that’s present with no known injury) is the suraspinatus. This rotator cuff muscle is located at the top of the shoulder. If you place your hand about half way between your neck and shoulder, you’ll feel your collar bone in the front and your shoulder blade in the back. The muscle in between is the supraspinatus. The supraspinatus runs out toward the shoulder, and before it gets to the arm bone, it runs underneath the end of the shoulder blade and collar bone. The space allowed for the supraspinatus in small, and any changes in the alignment of the shoulder blade can lead to pinching of the supraspinatus with all reaching, lifting, and overhead activities. This pinching is called Impingement, and it is very common.

More often than not, Impingement is what is hurting, and shoulder blade alignment and rotator cuff strength are the roots of the pain. In order to fix the pain, we need to address the roots of the problem. Strengthening the shoulder blade stabilizers by training them to pull the shoulder blade down and back on the trunk will open up the space where the supraspinatus travels under the bone, and strengthening the rotator cuff muscles will improve the efficiency of the shoulder joint itself. Combined, these exercises will enable to shoulder joint to move correctly and efficiently, decreasing the likelihood of pain and injury, and improving shoulder function with all mobility.

* A subluxation is when the ball slides out and quickly right back in to the socket, and a dislocation is when the ball slides out and gets stuck away from the socket.